Flash: Trevor Makhobas Great Temptation in the Garden comments on the disjointed power relationships that apartheid created.

Set in Durban and published after the Acts prohibiting mixed marriages were repealed, Lewis Nkosi’s Mating Birds explores the enduring pathology of racism and the devastation it wrought on individual lives. The similarly titled essay, curated by Gabi Ngcobo, Sumayya Menezes and Zinhle Khumalo, is on exhibition at the KwaZulu-Natal Society of the Arts Gallery. With the montaging of place, public memory and the archive, it marks a space of encounter between apartheid laws and the small, singular events in lives in the interstices between unjust and repressive laws.

The first Immorality Act was introduced in 1927 and the second in 1957 (renamed the Sexual Offences Act), followed by a number of amendments. In 1949 the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act was introduced and also amended. It was repealed by the 1985 Immorality and Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amendment Act.

The works in this exhibition “map the manner in which artists have intervened in the space of sexual politics”. The premise is set forth in a pedagogy of complexity, requiring viewers to suspend judgment and, instead, implicate themselves in the narrative.

The atmosphere of the gallery is cool and muted. The walls on the right are stark white, whereas those on the left of the lower level, situated beneath the cantilevered platform that makes up the upper level, are black. In white chalk at the bottom of the wall is a timeline of the Acts. The periods between 1957 and 1969 are interspersed with representations the increasing numbers of people arrested for sex across the colour line, until 1985.

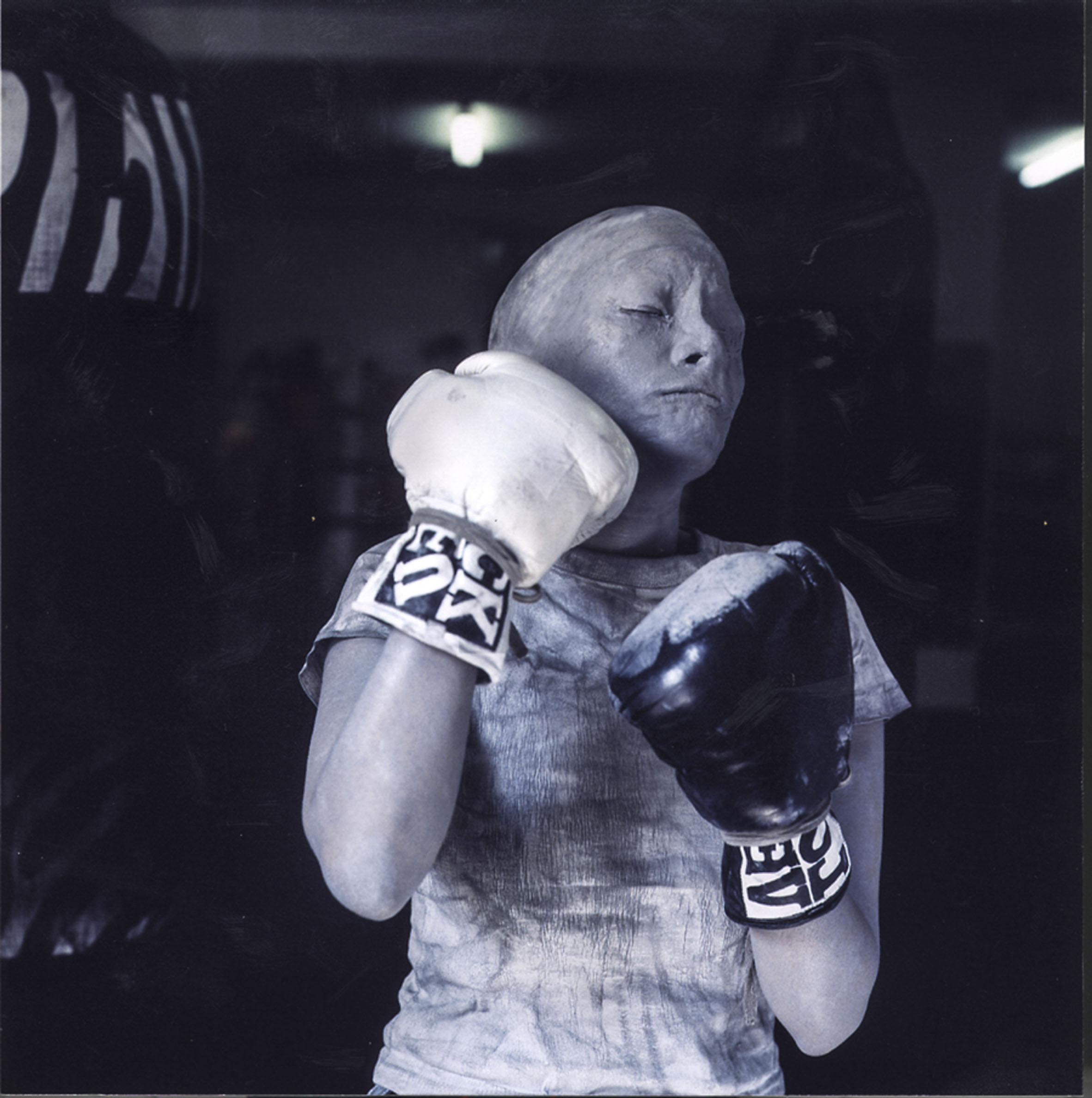

Above this timeline, the thesis is advanced in a series of paragraphs formed by clustering works together. For example, the grey-scale image of Tracey Rose’s Lovemefuckme (2001) — in which Rose’s masked face is contorted upward, with the mismatched gloves on her hands poised to deliver the next strike to her face — sits next to an A3 photocopy of pages 42 and 43 from Fanon’s much-quoted Black Skin, White Masks (1967). In these two pages, Fanon endeavours to race the perversions and imperfections of love by exploring a quotation that contends that, even in love, a woman of colour is “never altogether respectable in a white man’s eyes”.

Contradictions: Tracey Rose’s Lovemefuckme is juxtaposed with two pages from Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks.

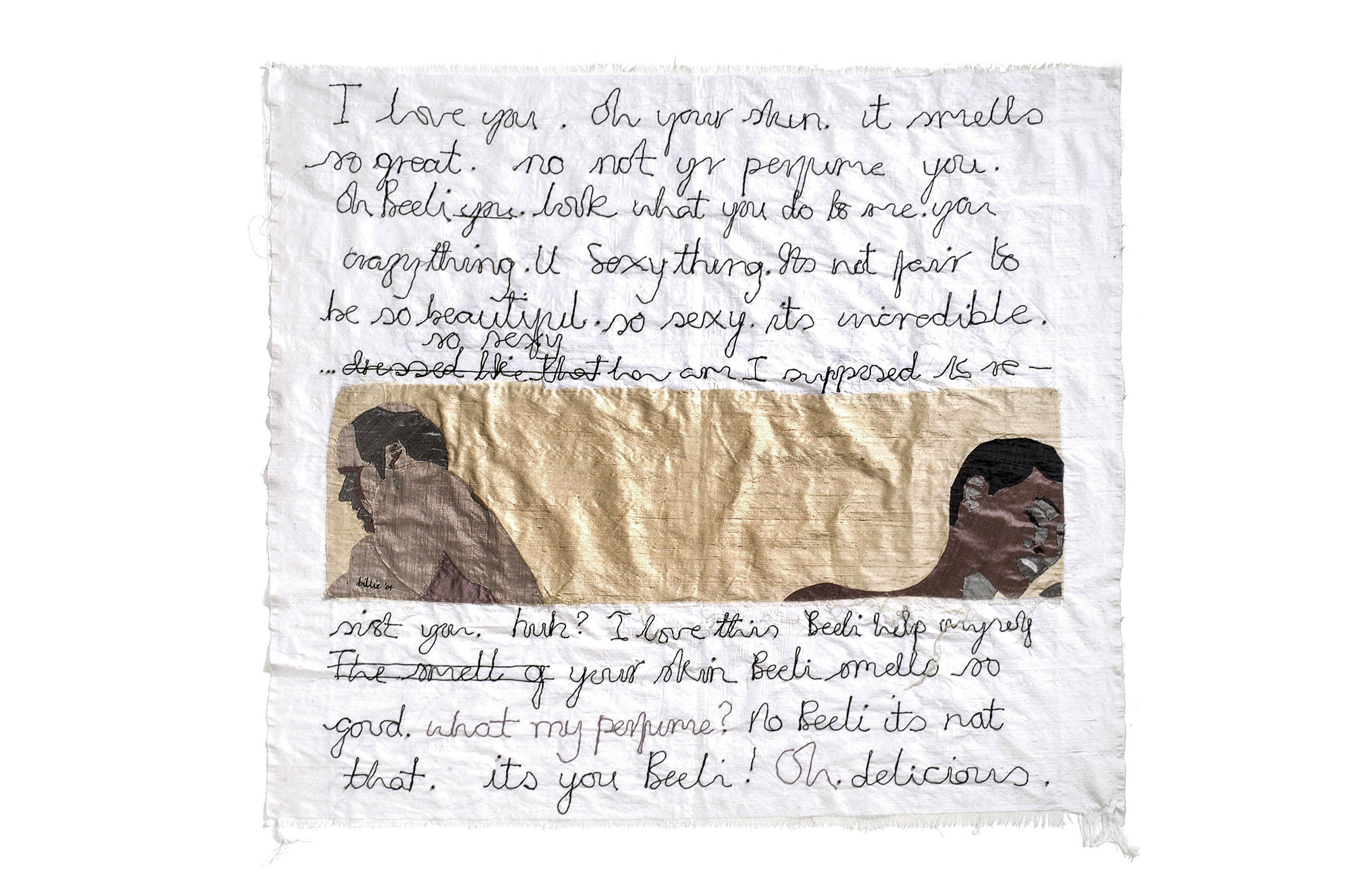

This is followed by Billie Zangewa’s Pillow Talk, presented as a colour reproduction containing erotic words often said in a postcoital embrace. In contrast to the erotic nature of the words, the lovers are turned away from each other, revealing some distance, perhaps discomfort or strain. When considering Pillow Talk next to the Fanon quote, they become explicitly exoticising and somewhat sinister.

Dualism: Billie Zangewa’s Pillow Talk creates a tension with the intimacy of the text, but the couple are physically distant.

The next paragraph is foregrounded by the Lebogang Mashile poem Kedi’s Song, next to which are A4-sized images of Zanele Muholi’s “Massa” and Mina(h) (2008), surrounded by excerpts from two academic texts. One analyses Zakes Mda’s The Madonna of Excelsior and the other examines whiteness.

Mda’s book tells of a sex scandal in the 1970s that rocked Excelsior in the Free State. Seven men and 14 women were arrested for participating in these sexual unions across the colour line that produced children.

Also drawing from the Excelsior scandal, Mashile’s poem evokes the tragic existence where one’s skin is the evidence of miscegenation and reminds one of the violent futility that was the life of Happy Sindane.

By placing the poem next to Muholi’s “Massa” and Mina(h) series, in which three maids are assertively positioned on chairs while a white man lies on the ground with his tie loose and shirt misshapen, one can infer that perhaps the Lolitas of Excelsior would have had everyday proximity to these men.

The nature of the intimate proximity is suggested in Muholi’s image and pieced together and unravelled in The Madonna of Excelsior, which incidentally positions the women as being maids, and their participation in the sex ring ranging from coerced to transactional.

As one traverses the grey concrete floor, one encounters the off-centred vitrine with its collection of supplementary evidence. These include colour photocopies, mounted on foam boards of varying sizes, of the 1983 cover of Mating Birds.

Among them is a United Nations photograph of people at the Durban beachfront in 1976. The vitrine also contains enlarged copies of the front pages of the 1927 Immorality Act, one of its amended versions, and the Act of 1985. Next to these is a newspaper article about the vitriolic social media comments about the marriage of Springbok captain Siya Kolisi to Rachel Smith.

As the documents are presented without sensationalism, the veneer of politeness is swept away and the cyclical nature of collective social dysfunction is laid bare. Like dirt swept beneath a carpet, the racist outbursts, delivered by social media, produce a familiar outrage, seemingly concerned less with the shame of the dirt being there, and more with the fact that it has been seen.

Apartheid’s heteronormative fixation is evident from the 1967 amendment of the Immorality Act , which dealt with homosexuality as an afterthought. In paragraph four, the essay describes a deliberate queering of the archive as a necessary action to liberate queer experiences and possibilities out of the archival closet.

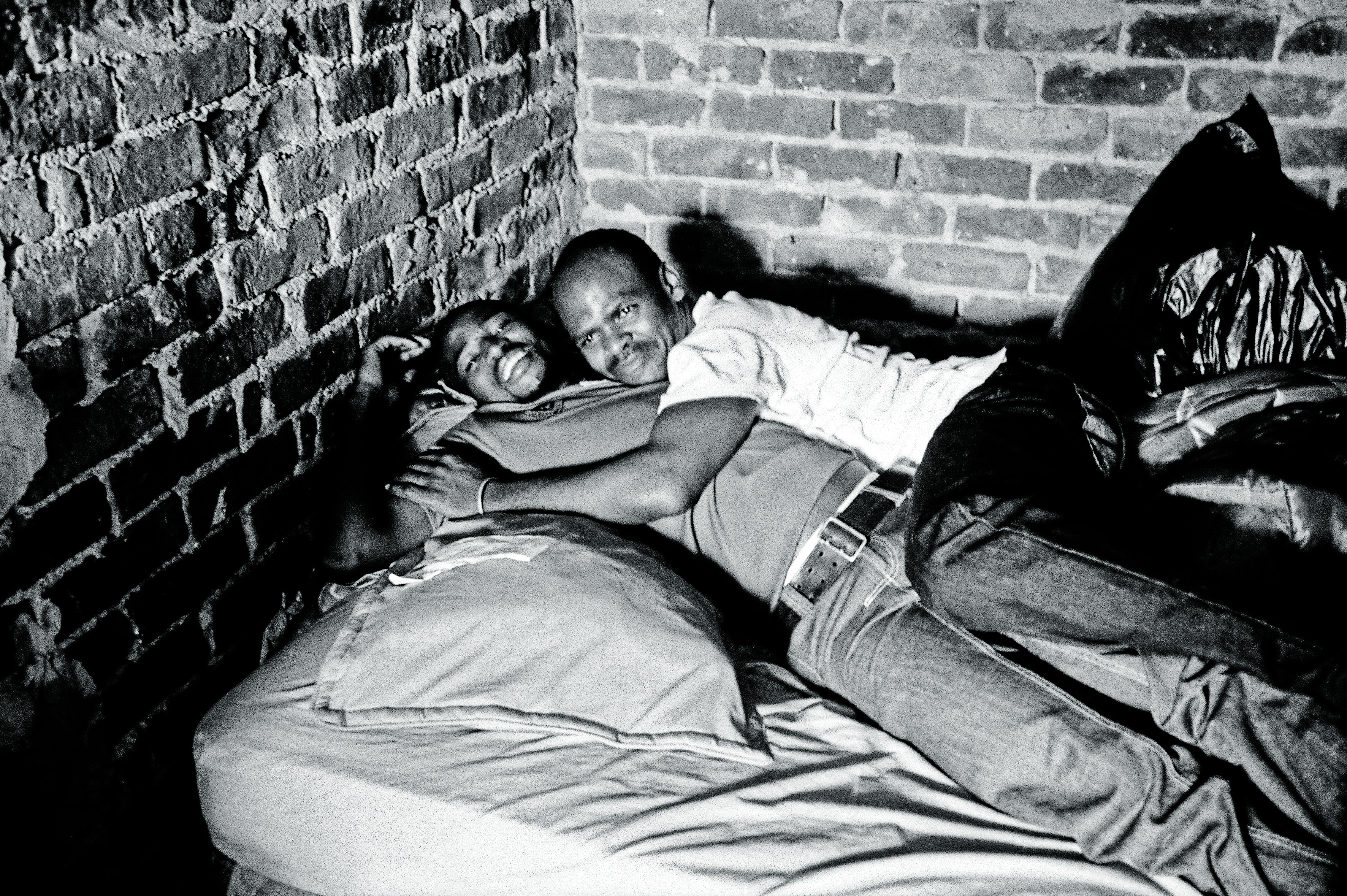

With this interweaving of the fictive and the personal, space opens up for queer subversion. This makes possible the reading of stories and narratives that would otherwise not have found direct expression. For example, Muholi’s “Massa” and Mina(h) is sexually charged and suggestive of same-sex desire, whereas photographer Sabelo Mlangeni’s Bafana Mhlanga and His Soccer Star Boyfriend (2009) presents two men, wide-eyed, caught in a tentative and cautious intimacy. The two lie in a warm embrace on a bed pushed up against the corners of a room, with joy and contentment on their faces.

Forbidden: Sabelo Mhlanga’s Bafana Mhlanga and His Soccer Star Boyfriend is placed next to an excerpt of a hate speech about homosexuality.

Between these works is an excerpt of a speech decrying the viperous spirit of homosexuality that threatens to ruin the moral fibre of Afrikanerness unless dealt with decisively. Next to this is a Rise and Fall of Apartheid catalogue open on a page on which a short account with images details how a magistrate and his colleagues performed voyeuristic duties to catch suspects in the act of contravening the Immorality Act.

In the upper level of the gallery we are presented with the sensitive personal letters of Simon Tseko Nkoli to his lover Roy Shepard. Written over four years while Nkoli was in prison, initially without being charged, and later while awaiting trial on treason charges. The letters, which reveal an intimacy sustained by an explicitly stated longing, are the transcripts published by the Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action organisation in 2007 and that form part of Gala’s archive.

The rest of the essay is advanced by the presentation of singular works from Dineo Bopape’s new film Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings] produced over several years and completed on the occasion of the 10th Berlin Biennale.

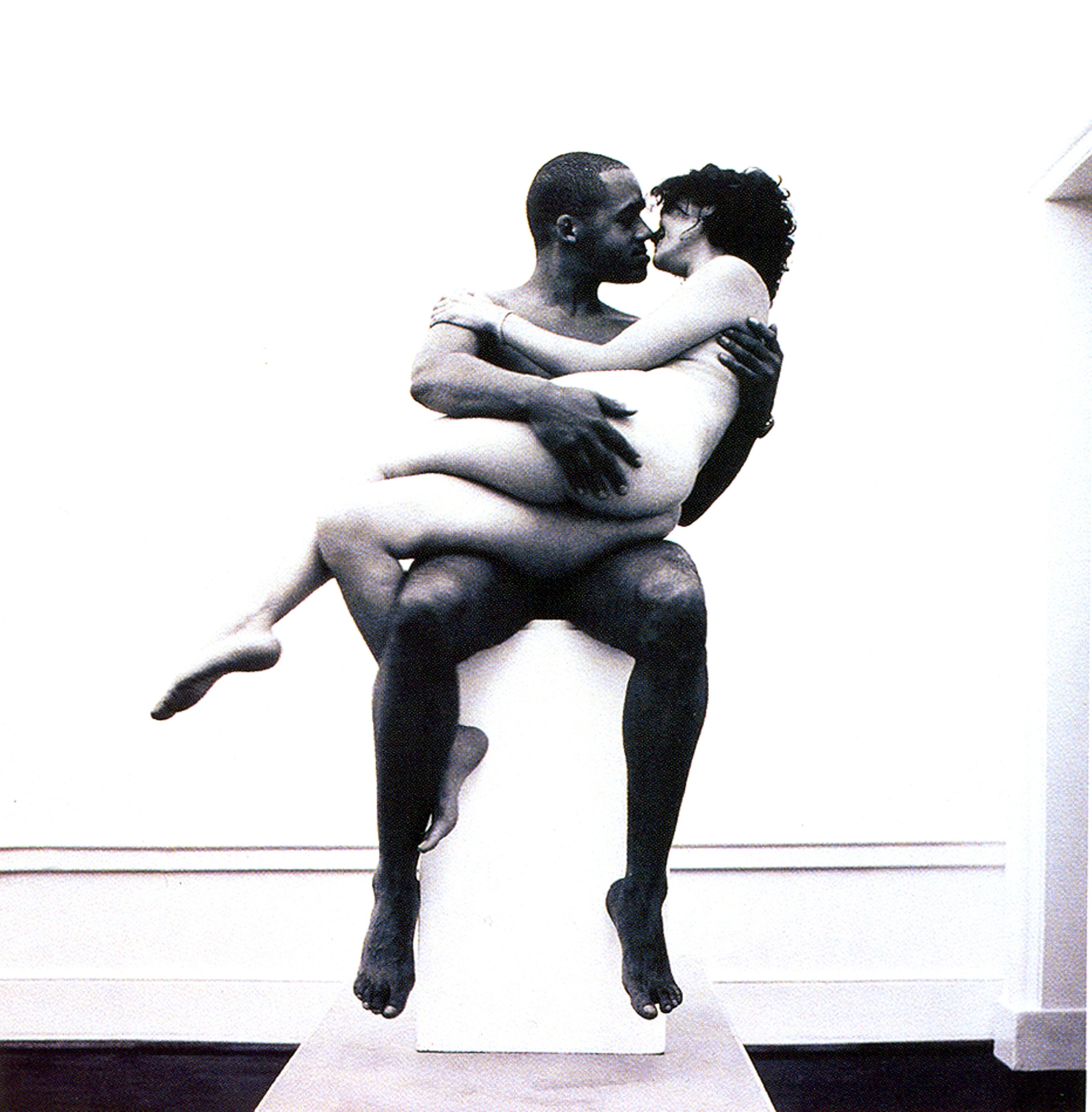

Alongside these are Rose’s The Kiss (2001), Lady Skollie’s Homage to Trevor Makhoba’s Studio Visit and Simnikiwe Buhlungu’s silkscreen banners proclaiming varying articulations of “We’re not making this up!” There is also Trevor Makhoba’s provocative 1995 work Great Temptation in the Garden.

Tracey Rose’s The Kiss crosses the colour line

On entering the upper level, one encounters Makhosazana Xaba’s poem You Told Me, which takes up a good part of the wall in matte amber vinyl. Elsewhere there is the consistent language of clusters for paragraphs, vitrines for supplementary information and writing low on the wall in white chalk for footnotes.

The intertextual nature of this essay offers multiple entry points, from the visual and the literary to the textual and disparate sources to arrive at a discursive moment that coalesces as the exhibition. Rather than simply looking at the images and works of art, the Immorality Act is explored in the cultural and social, as well as in personal accounts and configurations that are read in relation to each other.

The exhibition is intimate, dense, and requires a shift in our gaze, both in how we encounter these familiar works and how we look at the present manifestations of interpersonal violence in intimate relationships and the continued expression of toxic masculinities and fragile femininities. This is not to excuse them, but to exercise introspection and compassion when considering them. The exhibition communicates the complex and explorative sexual expressions that emerge from psychosocial atrocities driven by abuses of power, warped hierarchies and sexual oppression.

Mating Birds Vol.2 runs at the KZNSA until February 10